Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle del Hudson

Medio Ambiente

Land Acknowledgement

Por Antonio Pallares

April 2022At Bard College, like many other universities in the United States and Canada, several professors have included a Land Acknowledgement at the top of their curriculum that is read at the beginning of the semester.

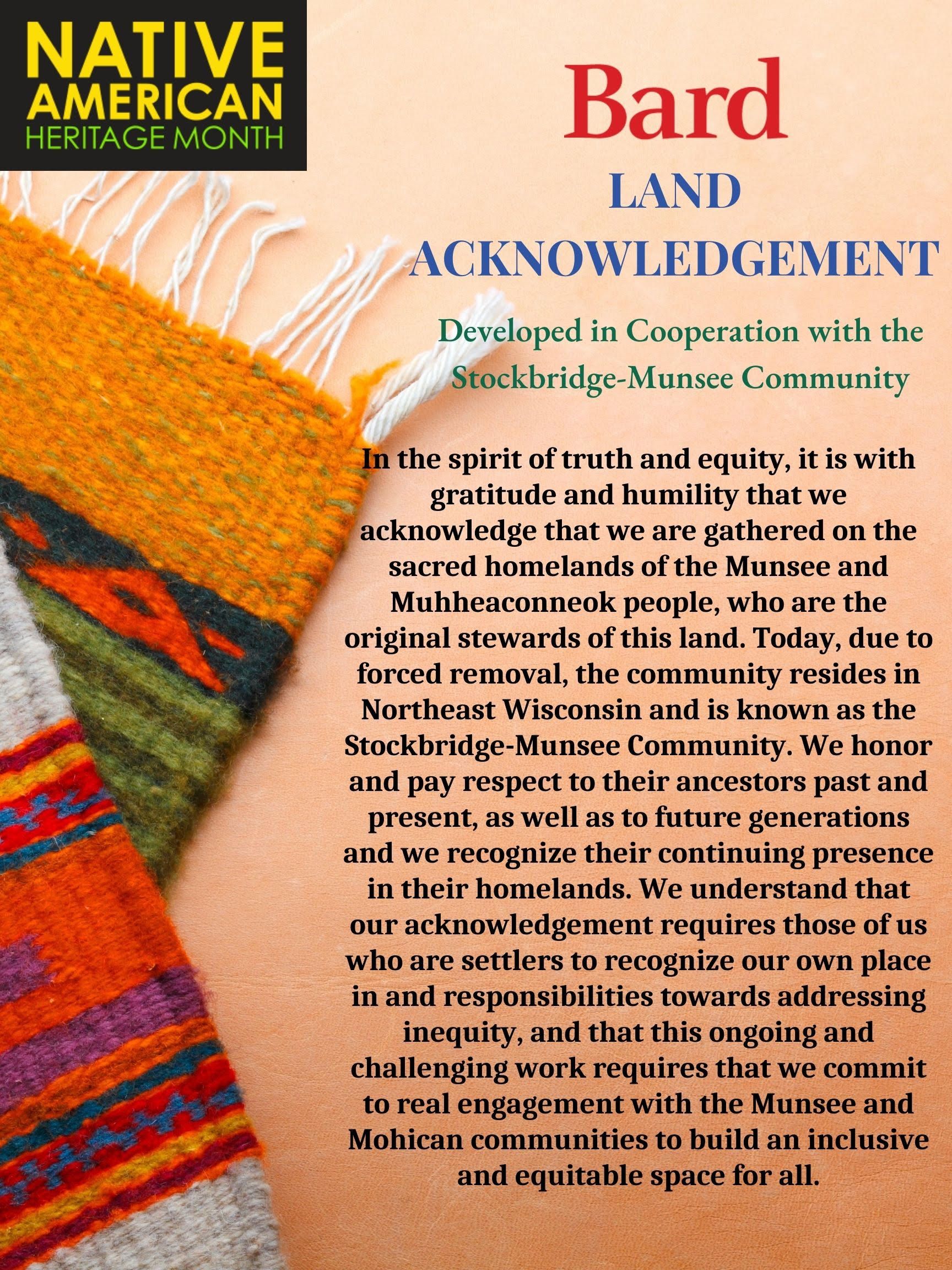

Bard's acknowledgment reads like this:

In the spirit of truth and equity, it is with gratitude and humility that we acknowledge that we are gathered on the sacred homelands of the Munsee and Muhheaconneok people, who are the original stewards of this land. Today, due to forced removal, the community resides in Northeast Wisconsin and is known as the Stockbridge-Munsee Community. We honor and pay respect to their ancestors' past and present, as well as to future generations and we recognize their continuing presence in their homelands. We understand that our acknowledgment requires those of us who are settlers to recognize our own place in and responsibilities towards addressing inequity and that this ongoing and challenging work requires that we commit to real engagement with the Munsee and Mohican communities to build an inclusive and equitable space for all.

The Land Acknowledgement is a short declaration that seeks to remember the presence and history of the original peoples of the lands that we inhabit today. Its purpose is to establish the commitment of an institution—such as a university, but not limited to that—in fighting against the inequities against these peoples. Although we work, study, and live in the Hudson Valley, many of us do not know much about the history of this land and the people who inhabited it, and continue to inhabit it before the arrival of the Europeans. This is due in large part to a tragic history of genocide and exile of millions of indigenous people, and the systematic oppression of their culture, which remains marginalized today.

In the United States as well as in Latin America, this disenfranchisement has made indigenous communities disproportionately vulnerable to poverty, and their marginalization has largely minimized their cultural contribution to society. We must recognize this history and express our commitment to equity and restoration of this millenary knowledge, especially when the climate change crisis has shown that our current way of operating, based on European principles, has destabilized nature. In a certain way, the land acknowledgment affirms something quite indisputable but that we often forget: the original peoples have been on these lands much longer than us, they know how to preserve them and prevent their deterioration.

For Dr. Kahan Sablo, Dean of Inclusive Excellence at Bard College, land acknowledgment is not the end but the beginning of a process of accountability and empowerment for positive change: “The next step is how to turn this into a statement based on action instead of complicity”. That is, recognition must be accompanied by some action directed towards equity. In Sablo's experience, for example, this is achieved by integrating Native Americans into inclusion proposals, such as the development of scholarships and college support for the Munsee-Muhheaconneok communities.

Working together with these communities enriches our knowledge of the Earth. This is of relevance for environmental movements, where greater interest has been generated in the ancestral knowledge of conservation and coexistence with nature that native peoples protect. In an interview on La Voz with Mariel Fiori on Radio Kingston and the spirit of historic reparations and natural restoration in the state of New York, indigenous activist Tiokasin Ghosthorse affirms that various individuals and companies took the initiative to return the land to indigenous people to preserve. In this way, cultural centers and museums have been created celebrating the native identity that is essential, as well as the land acknowledgment, to include and give a greater spotlight to the original nations in our collective consciousness.

The native peoples here do not have the same conception of property that we have; in times of unsustainable pollution and deforestation, perhaps it's best to rethink our surroundings for what they are—a common good. Furthermore, with a war that has left the environment as a secondary problem, perhaps we should, in Tiokasin's words, "Learn how to live with the land" since "if we can live in peace with the land, we can live in peace among ourselves”.

back to top

COPYRIGHT 2022

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

In the spirit of truth and equity, it is with gratitude and humility that we acknowledge that we are gathered on the sacred homelands of the Munsee and Muhheaconneok people, who are the original stewards of this land. Today, due to forced removal, the community resides in Northeast Wisconsin and is known as the Stockbridge-Munsee Community. We honor and pay respect to their ancestors' past and present, as well as to future generations and we recognize their continuing presence in their homelands. We understand that our acknowledgment requires those of us who are settlers to recognize our own place in and responsibilities towards addressing inequity and that this ongoing and challenging work requires that we commit to real engagement with the Munsee and Mohican communities to build an inclusive and equitable space for all.

The Land Acknowledgement is a short declaration that seeks to remember the presence and history of the original peoples of the lands that we inhabit today. Its purpose is to establish the commitment of an institution—such as a university, but not limited to that—in fighting against the inequities against these peoples. Although we work, study, and live in the Hudson Valley, many of us do not know much about the history of this land and the people who inhabited it, and continue to inhabit it before the arrival of the Europeans. This is due in large part to a tragic history of genocide and exile of millions of indigenous people, and the systematic oppression of their culture, which remains marginalized today.

In the United States as well as in Latin America, this disenfranchisement has made indigenous communities disproportionately vulnerable to poverty, and their marginalization has largely minimized their cultural contribution to society. We must recognize this history and express our commitment to equity and restoration of this millenary knowledge, especially when the climate change crisis has shown that our current way of operating, based on European principles, has destabilized nature. In a certain way, the land acknowledgment affirms something quite indisputable but that we often forget: the original peoples have been on these lands much longer than us, they know how to preserve them and prevent their deterioration.

For Dr. Kahan Sablo, Dean of Inclusive Excellence at Bard College, land acknowledgment is not the end but the beginning of a process of accountability and empowerment for positive change: “The next step is how to turn this into a statement based on action instead of complicity”. That is, recognition must be accompanied by some action directed towards equity. In Sablo's experience, for example, this is achieved by integrating Native Americans into inclusion proposals, such as the development of scholarships and college support for the Munsee-Muhheaconneok communities.

Working together with these communities enriches our knowledge of the Earth. This is of relevance for environmental movements, where greater interest has been generated in the ancestral knowledge of conservation and coexistence with nature that native peoples protect. In an interview on La Voz with Mariel Fiori on Radio Kingston and the spirit of historic reparations and natural restoration in the state of New York, indigenous activist Tiokasin Ghosthorse affirms that various individuals and companies took the initiative to return the land to indigenous people to preserve. In this way, cultural centers and museums have been created celebrating the native identity that is essential, as well as the land acknowledgment, to include and give a greater spotlight to the original nations in our collective consciousness.

The native peoples here do not have the same conception of property that we have; in times of unsustainable pollution and deforestation, perhaps it's best to rethink our surroundings for what they are—a common good. Furthermore, with a war that has left the environment as a secondary problem, perhaps we should, in Tiokasin's words, "Learn how to live with the land" since "if we can live in peace with the land, we can live in peace among ourselves”.

back to top

COPYRIGHT 2022

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

Comments | |

| Sorry, there are no comments at this time. |