Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle del Hudson

Once Upon a Time . . . Childcare in the Middle of the Pandemic

Por Nohan Meza

July 2020Mid-March, schools and daycares for children closed amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. While the country and the rest of the world were trying to figure out what was happening, the focus was on adults, not children. What kind of support did they lack during these times? What are the dangers and risks for their wellbeing that come with reopening the economy? What kind of future are we leaving for this young generation? These are the kind of questions that rise during uncertain times. And the answer isn’t clear, but a series of conversations with educators and teachers reveals that the answer begins at home, but extends far more, touching upon care centers and the systemic inequality that has plagued this country since its conception.

One of the biggest discrepancies regarding how children reacted to and interpreted the pandemic has to do with the economic status of their families and what kind of recreational space they have available. Maria Sachiko Cecire, Director of the Bard Center for Experimental Humanities and professor of children’s literature, explains one of the first exercises she gives to students in her class: “I give my students a piece of paper and ask them to draw a child, once they’re done, we talk about it. As you can imagine, the child is rarely a person of color, the gender is generally well defined, is usually outside and surrounded by commodities, and almost inevitably in every drawing they’re smiling. So when we think of the idea of ‘child,’ who is doing the thinking and what are the presumptions about childhood they’re bringing?” One can easily see the chasm that exists between the conventional conception of a child and the reality in which they live.

OUR ANXIETIES REFLECTED IN CHILDREN

Olga Maritza-Salazar, kindergarten teacher in public school and a regular contributor for La Voz, talks about the difficulties that some families went through and are still going through during this pandemic, and now some parents passed down some of these anxieties to the children. “I don’t want to make a racial distinction, but it’s almost as if the Latinx community was a little bit more . . . dramatic. They would say, ‘Don’t go outside ‘cause grandpa is old and he can die.’ It was the most drastic thing they could say to the kids to stop them. However, the non-Latinx kids would say things like, ‘My Mommy says this is contagious,’ and they had more explained to them alongside with more scientific reference regarding the virus. Besides you could see the difference: middle-class children would have bigger houses, they would have their own swing set in their backyards so they could go outside and play. More information was needed.”

The delayed reaction in the United States led to a lack of information in English, but even more so in Spanish, leading parents to drastic maneuvers in order to prevent the risk of their kids getting sick. Even then, with schools and care centers closed, many parents still had to work their essential jobs and not all of them had the option to work from home. “For some Latinx parents it was very difficult to do virtual learning. I had the case of a child whose home I called by chance, and he picks up the phone thinking it’s his mother. And when I said who I was, bam! he hung up the phone. That’s when you assume that the kid was by himself. I called again but the kid wouldn’t answer anymore. Working in a Hispanic program you see the reality of these issues, so like I said, for some parents it was very, very difficult.” But the problem wasn’t only dealing with technology or caring for the kids.

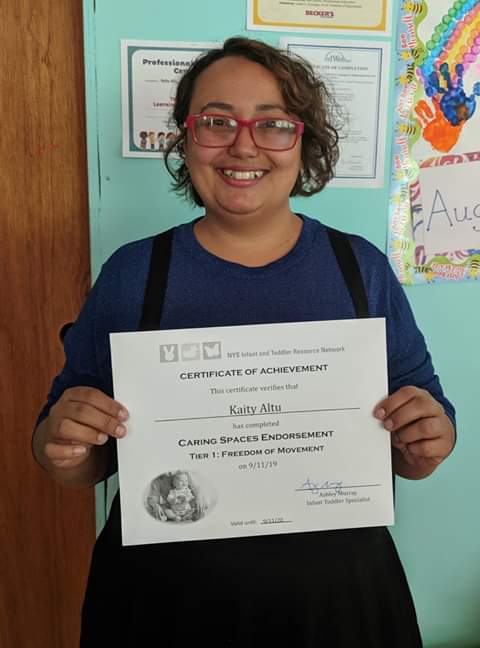

Kaity Altu, of Puertorican descent, is owner and director of Mountainrise Daycare in Lake Katrine, NY, and she claims that, while it’s true the government prepared relief aid packages for small businesses, not all businesses were considered, including hers. “Throughout this whole phase I’ve been trying to raise awareness on how challenging this has been for child daycares. For example, aid for small businesses like mine, are for businesses that have three or more people working. Here it’s just me. There were so many relief packages I couldn’t qualify for. I know Verizon was doing one, Facebook was doing another, and so was the Chamber of Commerce, but for none of those I qualified due to the fact that I’m the only employee. So as a whole this has been incredibly difficult for care providers, in particular child-care centers. And the big issue is, if all these care centers have to close due to a lack of funds, once businesses reopen and parents have to go to work, who’ll take care of the children?

Once it All Blows Over

It’s time we think about what kind of government we are leaving to the next generation, how that generation will be affected by the endemic failures of the systems in place. Many people likely share Olga Maritza-Salazar’s sentiment, that all this will one be, “a fairy tale. That once upon a time there was a sickness and kids couldn’t go outside and play, because if you did you could contract it and put your family at risk.” But that all depends on who wields the power to tell these stories.

According to the professor Maria Sachiko-Cecire, narratives can be easily manipulated: “If you look at the 1918 influenza epidemic, nationalistic narratives regarding the end of World War I completely eclipsed the reality of the global pandemic. It was more useful in order to maintain power to speak of the triumph of the Allied troops instead of addressing the failures of so many countries in keeping a huge amount of their citizens alive. So that story isn’t mentioned that much in books. In the same way, how we remember the COVID-19 crisis will depend on the political decisions we make regarding how we tell our story, and who has the power to decide how these stories get told.”

But there’s hope. There’s hope found in the extensive activism taking place and in the way we disseminate information and events. Maria continues, “One of the biggest moments of ‘awakening,’ so to speak, of the pandemic in the United States was when we began to see all these first-hand accounts of doctors who were writing about what was happening in their emergency rooms through tweets. Then these were shared on Facebook and later on through other platforms and then in one or two days you could already see them in newspapers. Thanks to digital narratives (people sharing their own anecdotes on social media, which can disseminate across the globe very quickly), beyond the pandemic, there seems to be heightened focus regarding racial inequality, suddenly there’s more interest tin paying attention to the personal experiences of others.”

We live in viral times, literally and metaphorically. We have the possibility and responsibility make sure that these failures don’t disappear under the shadow of history. The pandemic is not the cause of these issue but rather the cataclysm through racism and systemic inequality come to light. The only way in which all of these should resemble a fairy tale, is if one day we are able to arrive to that final line they all share . . . .

RESOURCES

My Hero is You - Kids book about the pandemic

Translated from Spanish by Nohan Meza

back to top

COPYRIGHT 2020

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

OUR ANXIETIES REFLECTED IN CHILDREN

Olga Maritza-Salazar, kindergarten teacher in public school and a regular contributor for La Voz, talks about the difficulties that some families went through and are still going through during this pandemic, and now some parents passed down some of these anxieties to the children. “I don’t want to make a racial distinction, but it’s almost as if the Latinx community was a little bit more . . . dramatic. They would say, ‘Don’t go outside ‘cause grandpa is old and he can die.’ It was the most drastic thing they could say to the kids to stop them. However, the non-Latinx kids would say things like, ‘My Mommy says this is contagious,’ and they had more explained to them alongside with more scientific reference regarding the virus. Besides you could see the difference: middle-class children would have bigger houses, they would have their own swing set in their backyards so they could go outside and play. More information was needed.”

The delayed reaction in the United States led to a lack of information in English, but even more so in Spanish, leading parents to drastic maneuvers in order to prevent the risk of their kids getting sick. Even then, with schools and care centers closed, many parents still had to work their essential jobs and not all of them had the option to work from home. “For some Latinx parents it was very difficult to do virtual learning. I had the case of a child whose home I called by chance, and he picks up the phone thinking it’s his mother. And when I said who I was, bam! he hung up the phone. That’s when you assume that the kid was by himself. I called again but the kid wouldn’t answer anymore. Working in a Hispanic program you see the reality of these issues, so like I said, for some parents it was very, very difficult.” But the problem wasn’t only dealing with technology or caring for the kids.

Kaity Altu, of Puertorican descent, is owner and director of Mountainrise Daycare in Lake Katrine, NY, and she claims that, while it’s true the government prepared relief aid packages for small businesses, not all businesses were considered, including hers. “Throughout this whole phase I’ve been trying to raise awareness on how challenging this has been for child daycares. For example, aid for small businesses like mine, are for businesses that have three or more people working. Here it’s just me. There were so many relief packages I couldn’t qualify for. I know Verizon was doing one, Facebook was doing another, and so was the Chamber of Commerce, but for none of those I qualified due to the fact that I’m the only employee. So as a whole this has been incredibly difficult for care providers, in particular child-care centers. And the big issue is, if all these care centers have to close due to a lack of funds, once businesses reopen and parents have to go to work, who’ll take care of the children?

Once it All Blows Over

It’s time we think about what kind of government we are leaving to the next generation, how that generation will be affected by the endemic failures of the systems in place. Many people likely share Olga Maritza-Salazar’s sentiment, that all this will one be, “a fairy tale. That once upon a time there was a sickness and kids couldn’t go outside and play, because if you did you could contract it and put your family at risk.” But that all depends on who wields the power to tell these stories.

According to the professor Maria Sachiko-Cecire, narratives can be easily manipulated: “If you look at the 1918 influenza epidemic, nationalistic narratives regarding the end of World War I completely eclipsed the reality of the global pandemic. It was more useful in order to maintain power to speak of the triumph of the Allied troops instead of addressing the failures of so many countries in keeping a huge amount of their citizens alive. So that story isn’t mentioned that much in books. In the same way, how we remember the COVID-19 crisis will depend on the political decisions we make regarding how we tell our story, and who has the power to decide how these stories get told.”

But there’s hope. There’s hope found in the extensive activism taking place and in the way we disseminate information and events. Maria continues, “One of the biggest moments of ‘awakening,’ so to speak, of the pandemic in the United States was when we began to see all these first-hand accounts of doctors who were writing about what was happening in their emergency rooms through tweets. Then these were shared on Facebook and later on through other platforms and then in one or two days you could already see them in newspapers. Thanks to digital narratives (people sharing their own anecdotes on social media, which can disseminate across the globe very quickly), beyond the pandemic, there seems to be heightened focus regarding racial inequality, suddenly there’s more interest tin paying attention to the personal experiences of others.”

We live in viral times, literally and metaphorically. We have the possibility and responsibility make sure that these failures don’t disappear under the shadow of history. The pandemic is not the cause of these issue but rather the cataclysm through racism and systemic inequality come to light. The only way in which all of these should resemble a fairy tale, is if one day we are able to arrive to that final line they all share . . . .

RESOURCES

My Hero is You - Kids book about the pandemic

Translated from Spanish by Nohan Meza

back to top

COPYRIGHT 2020

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

Comments | |

| Sorry, there are no comments at this time. |