Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle del Hudson

Buen Gusto

The Women's Republic

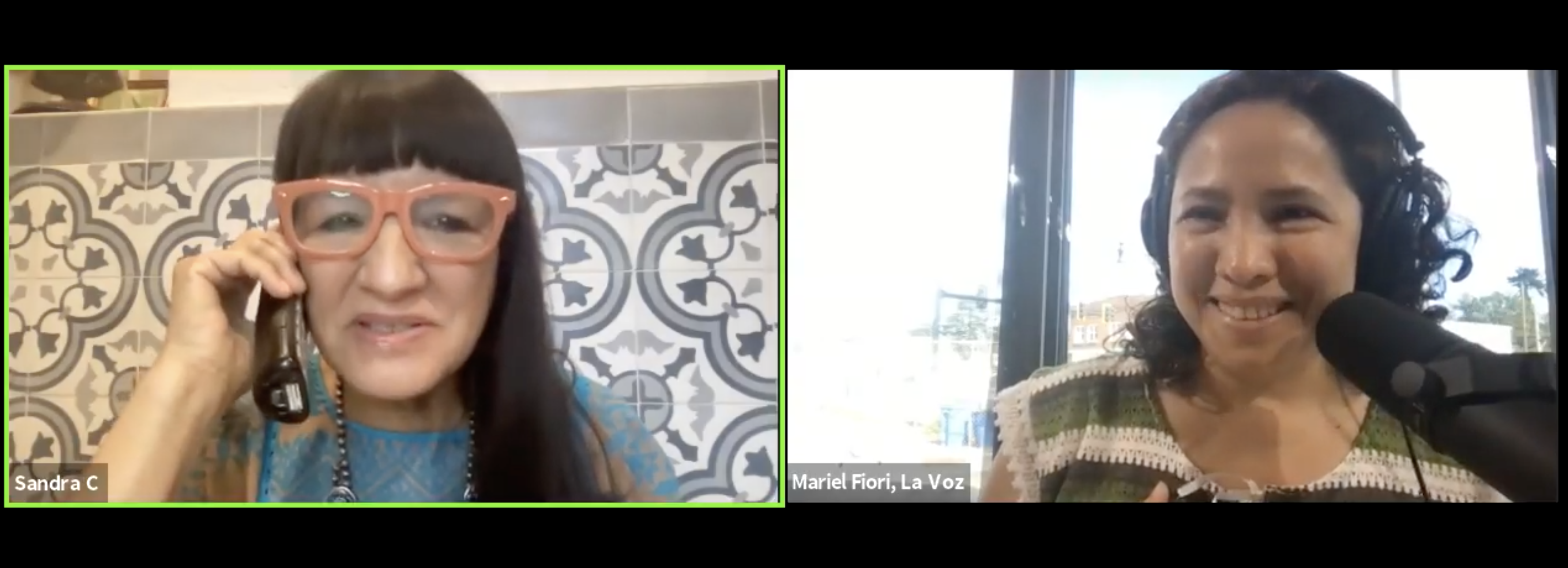

An interview with Sandra Cisneros

Por Mariel Fiori

March 2022 The novel The House on Mango Street made her very famous, with six million copies sold, translated into 20 languages, and currently a mandatory reading in elementary, secondary, and university schools in the United States. With more awards and published works than can be counted here, one of the most recognized writers in the United States, Sandra Cisneros spoke with La Voz about her most recent work, the bilingual “novelita”: Martita, I Remember You.

Mariel Fiori: I read your most recent work, Martita, I remember you. A lot of nostalgia since I'm from Argentina, and I read about young people in Paris, and I said "wow” this happened to me a little bit. Not the same, not the details, but the emotions did. How did you achieve this?

Sandra Cisneros: I believe in the stories of people who migrate to another country and who feel uncomfortable, have to endure and struggle to survive. This is the story of the women's republic, of the immigrants, of the poor, of all those who have suffered and endure to go on, right? And it happened to me when I lived and wrote the story, some are combinations of various people I met, women I met in my travels. When I lived in Paris, I understood the life of my father: I am the daughter of immigrants, of a man who ran away from home during World War Two, and went to the United States as a vagabond and he would tell me that sometimes he did not have enough to eat, he was robbed, and many other very strong stories. And it was that way that I understood his story: when I arrived like that, without money, without understanding the language, and sleeping on the floor, I understood the life of my father, and of all immigrants today with this part of my life that I lived as a vagabond in Paris in the early 80's and it affected me strongly, but it was so strong that I still feel a lot of compassion for the immigrant.

Tell us about your creative process.

To write I always start with an emotion, with something very strong. Maybe something I want to forget. For me that's the most important thing, to write about what you want, because it's a way to transform your demons into illuminations. It is very healing, it is very strong medicine. That's why I do it, that's why I'm healthy. And I start this way with a very strong emotion because the truth is that there was a Martita from Buenos Aires in my life that I lost. Over the years I met several women in the world, when I was trying to free myself from the fear that my father put in me, and I met some Mexican women, some from Yugoslavia, from several countries. I met Italian women, everywhere I traveled because I took the plunge with a scholarship I was given at the age of 28. I learned a lot, and more than anything I learned the stories that the women shared because we became friends in our time of need. And people who have nothing, they give you the most, don't they? And that's what I started writing about. I started with that memory of that Martita, of the women who were so beautiful, so generous to me, and then it swelled, the story got bigger. I pasted a little piece of the story of my cousin, my students and it became a little novel.

I read it in Spanish, and I loved it because there’s all the accents when the characters speak. How did you managed it in English to reflect those accents?

I steal the stories that people tell me, so the words, when they are put on the air, I go after that and when I write in English I try to imitate, even if it is in English, the way people speak. In this case, we have Paula who is Italian but mixes her Italian with English and Spanish and Martita, from Argentina, from Buenos Aires, we also have the boys who are porteños, Martita's dad, Mexican, and her husband, Ricardo who speaks English. So I tried to mix it up and write it this way. And I also have friends from Argentina who helped me, to see if it read well. And my wonderful translator, Liliana Valenzuela, I have to thank Liliana because yesterday we celebrated 30 years working together as writing colleagues and she is the best translator in the world because she is a poet, a storyteller, an essayist and she is also an angel. So I was not lacking anything.

What was it like to be the only female child in a family of so many male siblings when you were young?

The luck I had was to be my father 's favorite child. My father and I understood each other very well, we were like twins, we understood each other. But he had his ideas about how I should live my life, and I had my plan to be a writer. I don't know where that plan came from, but I kept it secret in my heart, I loved to read. I started writing poetry and stories in sixth grade, and I didn't say them out loud. But I kept it deep in my heart, and my dad, as a gentleman of his time, thought it was good when I told him I wanted to study at the university, because in his generation Mexican women of his class did it to find a husband, and that's why he encouraged me to go to the university. But after studying four years for my bachelor's degree and two more for my master's degree, my father scolded me, "You wasted all those years!” But at the end of his life we managed to understand each other, because he survived to see my success, he saw very hard times, when I had no money, I slept on the floor, I went from one chambita to another, from one state to another with my belongings, with my boxes. But at the end of his life he managed to understand why I made the sacrifice I did, and we understood each other. And at the end he told me "m'ija don't get married, they are going to take your pennies". At that moment I felt like I had triumphed. Everything I did in my life was for his approval, but he couldn't or wouldn't read my work. So it was very nice in the end.

There is a lot to talk about regarding women in literature, what we are (not) taught, and what we must unlearn. How do you change this with your writing?

I didn't find those until after I left college. When I studied, for example, I was lucky enough to have a very good teacher in high school who introduced me to Latin American literature, but of course, almost everything was by men. Except for Gabriela Mistral, a little bit of Alfonsina Storni. And we didn't get any of the cool women like Juana Inés de La Cruz, or Elena Garro, or Elena Poniatowska, there are so many. I didn't find those until after I left my studies at the university. I am grateful for the male writers who inspired me like Borges, Juan Rulfo, Manuel Puig, for example, but I feel like now at 66 years old there are not many years left and I should focus on women especially. Especially now in Mexico, where I moved to about 8 years ago. I don't know anything, I'm very slow when it comes to women's literatures because they don't make it into English, they are the last ones that they always try to translate. They translate the men first and forget the women, don't they? So at this point I feel like I'm in Kindergarten, starting to read, trying to read the women in Spanish, which I have a hard time with, but I try to read them in English first, and then I jump into the original. I want to read these women because they give me permission, they give me encouragement, they give me courage, to keep writing my stories from the point of view of a woman, of a daughter, of an immigrant, dual nationality, two languages.

The theme of home has been present in your work, from La Casa en la calle Mango, to this last one, Martita, Te Recuerdo.

I believe that all women look for a home that is ours. Not only physically, but also psychologically because we are born into a society where the culture, the church, the system, tell us what it means to be a good woman and we never have that space to describe ourselves without that prejudice in our heads. So for me a home of my own does not mean only the physical space of a house, but the psychological space that gives us permission to discover ourselves. And for me that own house exists in women's literature, that's why I look for women's works, because I feel that we as women live in a republic of women with the same dreams, the same problems, and we have more in common as women than men in our own country, don't we?

Could you give some advice for young women writers?

For women I'm going to tell everyone that the first thing is to earn your own money, so you have to study because maybe you're not going to make a dime as a writer and don't expect a dime. So, if you get something, that's nice, but if you don't, don't faint. Second, control your fertility: neither the government, nor the Pope, nor the church, nor the society, are going to take care of your child, so control your fertility according to your beliefs. And the third thing, don't despair if you don't have a boyfriend or if you don't have a date for Saturday, because solitude is necessary for you to develop yourself.

*Listen here to the full interview with Sandra Cisneros on La Voz with Mariel Fiori on Radio Kingston, in Spanish.

Cisneros visits the Hudson Valley

The NEA Big Read Hudson Valley is taking place this April around the book The House on Mango Street. It brings a series of events in collaboration between Bard College, La Voz magazine, Bard MAT, Radio Kingston, Bard Conservatory, Conjunctions literary magazine, Kingston, Red Hook, Tivoli, Rhinebeck libraries, the Reher Center for Immigrant History and Culture, and two local bookstores, Rough Draft and Oblong. There will be readings, groups, puppets, writing workshops, panels, performances of some of the vignettes from the novel that tells the story of life from the perspective of an immigrant girl and more. Cisneros herself will be around on those days. The full calendar can be found here.

COPYRIGHT 2022

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

Sandra Cisneros: I believe in the stories of people who migrate to another country and who feel uncomfortable, have to endure and struggle to survive. This is the story of the women's republic, of the immigrants, of the poor, of all those who have suffered and endure to go on, right? And it happened to me when I lived and wrote the story, some are combinations of various people I met, women I met in my travels. When I lived in Paris, I understood the life of my father: I am the daughter of immigrants, of a man who ran away from home during World War Two, and went to the United States as a vagabond and he would tell me that sometimes he did not have enough to eat, he was robbed, and many other very strong stories. And it was that way that I understood his story: when I arrived like that, without money, without understanding the language, and sleeping on the floor, I understood the life of my father, and of all immigrants today with this part of my life that I lived as a vagabond in Paris in the early 80's and it affected me strongly, but it was so strong that I still feel a lot of compassion for the immigrant.

Tell us about your creative process.

To write I always start with an emotion, with something very strong. Maybe something I want to forget. For me that's the most important thing, to write about what you want, because it's a way to transform your demons into illuminations. It is very healing, it is very strong medicine. That's why I do it, that's why I'm healthy. And I start this way with a very strong emotion because the truth is that there was a Martita from Buenos Aires in my life that I lost. Over the years I met several women in the world, when I was trying to free myself from the fear that my father put in me, and I met some Mexican women, some from Yugoslavia, from several countries. I met Italian women, everywhere I traveled because I took the plunge with a scholarship I was given at the age of 28. I learned a lot, and more than anything I learned the stories that the women shared because we became friends in our time of need. And people who have nothing, they give you the most, don't they? And that's what I started writing about. I started with that memory of that Martita, of the women who were so beautiful, so generous to me, and then it swelled, the story got bigger. I pasted a little piece of the story of my cousin, my students and it became a little novel.

I read it in Spanish, and I loved it because there’s all the accents when the characters speak. How did you managed it in English to reflect those accents?

I steal the stories that people tell me, so the words, when they are put on the air, I go after that and when I write in English I try to imitate, even if it is in English, the way people speak. In this case, we have Paula who is Italian but mixes her Italian with English and Spanish and Martita, from Argentina, from Buenos Aires, we also have the boys who are porteños, Martita's dad, Mexican, and her husband, Ricardo who speaks English. So I tried to mix it up and write it this way. And I also have friends from Argentina who helped me, to see if it read well. And my wonderful translator, Liliana Valenzuela, I have to thank Liliana because yesterday we celebrated 30 years working together as writing colleagues and she is the best translator in the world because she is a poet, a storyteller, an essayist and she is also an angel. So I was not lacking anything.

What was it like to be the only female child in a family of so many male siblings when you were young?

The luck I had was to be my father 's favorite child. My father and I understood each other very well, we were like twins, we understood each other. But he had his ideas about how I should live my life, and I had my plan to be a writer. I don't know where that plan came from, but I kept it secret in my heart, I loved to read. I started writing poetry and stories in sixth grade, and I didn't say them out loud. But I kept it deep in my heart, and my dad, as a gentleman of his time, thought it was good when I told him I wanted to study at the university, because in his generation Mexican women of his class did it to find a husband, and that's why he encouraged me to go to the university. But after studying four years for my bachelor's degree and two more for my master's degree, my father scolded me, "You wasted all those years!” But at the end of his life we managed to understand each other, because he survived to see my success, he saw very hard times, when I had no money, I slept on the floor, I went from one chambita to another, from one state to another with my belongings, with my boxes. But at the end of his life he managed to understand why I made the sacrifice I did, and we understood each other. And at the end he told me "m'ija don't get married, they are going to take your pennies". At that moment I felt like I had triumphed. Everything I did in my life was for his approval, but he couldn't or wouldn't read my work. So it was very nice in the end.

There is a lot to talk about regarding women in literature, what we are (not) taught, and what we must unlearn. How do you change this with your writing?

I didn't find those until after I left college. When I studied, for example, I was lucky enough to have a very good teacher in high school who introduced me to Latin American literature, but of course, almost everything was by men. Except for Gabriela Mistral, a little bit of Alfonsina Storni. And we didn't get any of the cool women like Juana Inés de La Cruz, or Elena Garro, or Elena Poniatowska, there are so many. I didn't find those until after I left my studies at the university. I am grateful for the male writers who inspired me like Borges, Juan Rulfo, Manuel Puig, for example, but I feel like now at 66 years old there are not many years left and I should focus on women especially. Especially now in Mexico, where I moved to about 8 years ago. I don't know anything, I'm very slow when it comes to women's literatures because they don't make it into English, they are the last ones that they always try to translate. They translate the men first and forget the women, don't they? So at this point I feel like I'm in Kindergarten, starting to read, trying to read the women in Spanish, which I have a hard time with, but I try to read them in English first, and then I jump into the original. I want to read these women because they give me permission, they give me encouragement, they give me courage, to keep writing my stories from the point of view of a woman, of a daughter, of an immigrant, dual nationality, two languages.

The theme of home has been present in your work, from La Casa en la calle Mango, to this last one, Martita, Te Recuerdo.

I believe that all women look for a home that is ours. Not only physically, but also psychologically because we are born into a society where the culture, the church, the system, tell us what it means to be a good woman and we never have that space to describe ourselves without that prejudice in our heads. So for me a home of my own does not mean only the physical space of a house, but the psychological space that gives us permission to discover ourselves. And for me that own house exists in women's literature, that's why I look for women's works, because I feel that we as women live in a republic of women with the same dreams, the same problems, and we have more in common as women than men in our own country, don't we?

Could you give some advice for young women writers?

For women I'm going to tell everyone that the first thing is to earn your own money, so you have to study because maybe you're not going to make a dime as a writer and don't expect a dime. So, if you get something, that's nice, but if you don't, don't faint. Second, control your fertility: neither the government, nor the Pope, nor the church, nor the society, are going to take care of your child, so control your fertility according to your beliefs. And the third thing, don't despair if you don't have a boyfriend or if you don't have a date for Saturday, because solitude is necessary for you to develop yourself.

*Listen here to the full interview with Sandra Cisneros on La Voz with Mariel Fiori on Radio Kingston, in Spanish.

Cisneros visits the Hudson Valley

The NEA Big Read Hudson Valley is taking place this April around the book The House on Mango Street. It brings a series of events in collaboration between Bard College, La Voz magazine, Bard MAT, Radio Kingston, Bard Conservatory, Conjunctions literary magazine, Kingston, Red Hook, Tivoli, Rhinebeck libraries, the Reher Center for Immigrant History and Culture, and two local bookstores, Rough Draft and Oblong. There will be readings, groups, puppets, writing workshops, panels, performances of some of the vignettes from the novel that tells the story of life from the perspective of an immigrant girl and more. Cisneros herself will be around on those days. The full calendar can be found here.

COPYRIGHT 2022

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

Comments | |

| Sorry, there are no comments at this time. |