Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle del Hudson

Su Dinero

Currency of Liberation, Community Currency

Por María Julia Hernández Sáez

February 2020 Over a period of eight days in San Juan, Puerto Rico, a recurring, yet unique sight took place. Every day in the sense that there were people in line to take money out of an ATM. Unique because they were hundreds of persons that got emotional when receiving the money, sometimes to the point of tears. They did not endure the long wait due to what they could buy with this money, but for the money itself. This is because this was not just any money, it was a cultural symbol and those tears represented the cultural pride of the Puerto Rican nation.

It happened during the presentation of the project Value and Change (“Valor y Cambio”), created by the Artist, Cinematographer, and intellectual, Frances Negrón-Muntaner. As she explained in the talk that I attended at Bard College last November, this project consisted on developing bills inspired on important figures of the Puerto Rican culture to fight the lack of trust amongst Puerto Ricans and provoke that they reconsider what they truly value. It had an artistic-cultural focus, not economic, and the participants joined the project as a sort of national vindication, to acquire cultural wealth, not economic.

However, the economic aspect of a monetary system is undeniable, and its creation was in part due to the economic crisis in Puerto Rico. Like Negrón-Muntaner says, “Puerto Rico doesn’t have a debt crisis, it has an austerity crisis.” In 1996, Puerto Rico entered a ten-year period of gradual elimination of tax exemptions, which hurt the development of private industry. In response, the government started to sell vulture funds, selling sectors of the Puerto Rican economy to industries and individuals with private interests. This practice led to the implosion of the fiscal crisis, but because Puerto Rico is considered a “non-incorporated territory” by the United States’ government, it cannot declare itself in bankruptcy and it is obliged to pay the debt as its utmost priority. Negrón-Muntaner identifies this method as the American model of “new extraction of colonial capital: debt.” Among the most worrisome, “this new modality of capital does not need Puerto Ricans,” leading to the concept of “Empty Island,” meaning, both the Puerto Rican economy and government work solely to pay the debt and not for its inhabitants.

Part of what inspired the project was the lack of trust that Negrón-Muntaner noticed in Puerto Rican society towards media and government platforms, and between the people. The project was reformulated after Hurricane Maria due to the lack of governmental support during the disaster. The Puerto Rican people developed a solidary economy in their communities and people survived “practicing an economy of exchange.” Puerto Ricans are capable of subsisting economically independent from the colonial capitalist economy that led to the crisis. Negrón-Muntaner asked herself “How does money acquire value? Can it be destructive?” and concluded that money, in essence, serves to “facilitate relations between people.”

While recruiting businesses to participate in the project, Negrón-Muntaner noticed that no one had heard of the concept “social currency” before but that they all understood it immediately. In the midst of the economic crisis and in spite of being informed that they could lose money and time for eight days, most businesses agreed to participate. The selection of the people that would go on the bills was based on four values: equity, solidarity, justice, and creativity. They also made an ATM machine called VYC (“Valor y Cambio,” or Value and Change) for it to be a physical experience.

In order to get the bills from the ATM, the participants had to answer the question: what do you value? The project was a success and people waited for hours to get the bills, being moved by answering the question, at times to the point of tears. From this surged what Frances Negrón-Muntaner recognized as “decolonial joy” defined as, “the possibility of a different future, one in which neither colony nor colonialism can define happiness.” Negrón-Muntaner witnessed this joy in “the exact moment when the participant received the bill, particularly the one they had waited for.” One of the participants, Eduardo Paz, Afro-Puerto Rican teacher, waited for the bill of the Cordero siblings and said: “This represents who I am,” expressing a dual valuation, “the world valued what he valued, therefore, the world valued him,” explained Negrón-Muntaner.

The people thanked her, not for her effort but for her joy. Negrón-Muntaner awards this to a triple plain of the Puerto Rican society caused by the austerity, Hurricane María, and the mass emigration. It has become important “to share not suffering, but joy.” More than a thousand participants did not use their bills, and they said it was because the bills were beautiful, they saw them as something that upholds “the identity and cultural pride” and it freed them from colonial capital, since “the dollar is seen as colonizing,” explained Negrón-Muntaner. She noticed that both hope, which is future oriented, and joy, which is present oriented, surged simultaneously. This feeling persisted in some of the participants, with the Puerto Rican community Caño Martín Peña launching their own community currency (the first one in Puerto Rico) only months after this project.

Negrón-Muntaner did not create this project with the intention of creating a sustentative economic alternative to the US dollar in Puerto Rico, but as “a way of starting a conversation”. She considers that the substitution of one currency by another does not solve the problems of necessity and inequality in society, but by valuing the experience instead of the money this liberation she calls decolonial joy took place. There will soon be a movie about the project.

Abundance in the Hudson Valley

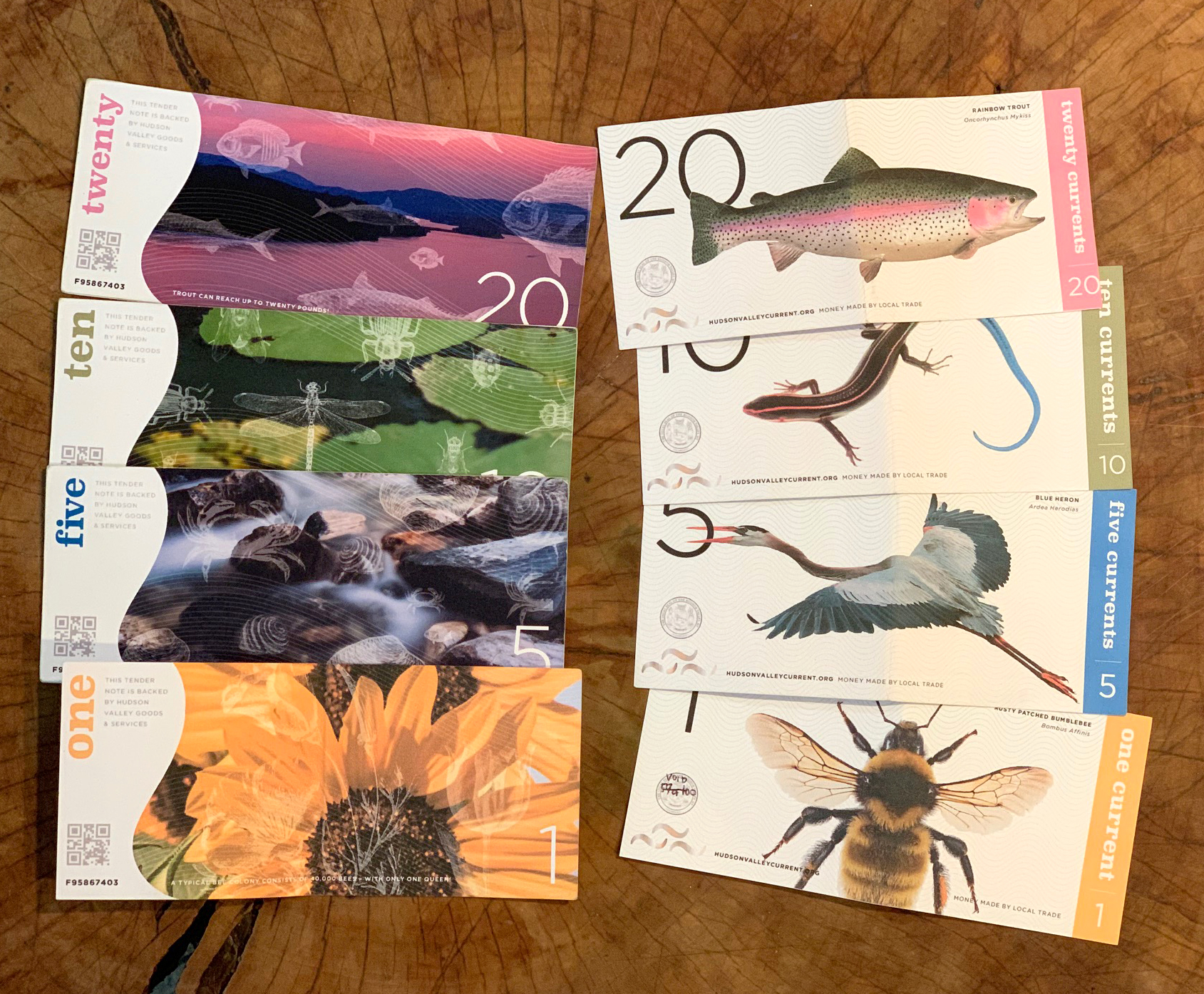

There is a social currency in our own Hudson Valley focused on strengthening the connections in the community and providing both businesses and individuals the freedom of get on economically in a local way and giving Hudson Valley the opportunity of generating earnings that remain in the valley and benefit our communities directly. The money exchanged from “Hudson Valley Current” remains circulating in the local economy and results in the development of the local economy.

Differently from “Valor y Cambio”, Hudson Valley Currents has an economic focus instead of an artistic-cultural one. While interviewing Chris Hewitt, the Co-founder and Executive Director of the currency, I discovered the magnitude of this currency’s impact and how it works inside our communities. Hewitt got inspired to start the currency to “Help people be more successful, reveal abundance, and inspire them to share and care for the community.”

With the goal of achieving local economic resilience, Hewitt recounts how he created this currency. “Working with a group of founders, we began to join our first members with our existing social media. Some of the first members were sponsors, since it is important to have something to purchase. Members bring people with them. Today we have around 400 members and almost 1 million currents have been exchanged in the past seven years,” narrates Hewitt.

For future participants, Hewitt talks of the importance of joining as a community, of his hyper-local focus, for the money to remain within the community for the most time possible and “this currency guarantees this.” It is the perpetual multiplier effect, says Hewitt and explains that six months ago he hired an Economics professor from Bard College, Leanne J. Ussher, to do a web analysis of Hudson Valley Current. She analyzed the information compiled in seven years and her analysis illustrated this perpetual multiplier effect. There are five affinity groups that support themselves mutually.

This currency is no longer solely virtual, since last October you can obtain bills at the Kingston Hudson Valley Current office. Among his aspirations, Hewitt wants to expand the current to more counties in the Hudson Valley. Right now, they are in Ulster and Dutchess, they have just expanded to Columbia, and have five members between Sullivan and Orange. “We want that wherever you go you see a Hudson Valley Current sign on the window,” dreams Hewitt.

According to Hewitt, Hudson Valley Current is the local currency with the most accelerated growth globally. Hudson Valley Current also has the Livelihood Magazine, a guide through the local economy, and the campaign “Satisfy Hunger”, a local initiative for food security. As federal law states, one current equates to one dollar and it pays taxes. 10% of Hewitt’s salary is payed in currents (his goal is to be payed 90% of his salary in currents) and for at least ten people to receive part of their salaries in currents too. Members use currents to pay rent, buy groceries, and in their daily lives.

You can live your own decolonial joy through the currents and in the meanwhile support the local economy. For more information about Hudson Valley Current and how to participate visit hudsonvalleycurrent.org.

Translated from Spanish by Nohan Meza COPYRIGHT 2020

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

However, the economic aspect of a monetary system is undeniable, and its creation was in part due to the economic crisis in Puerto Rico. Like Negrón-Muntaner says, “Puerto Rico doesn’t have a debt crisis, it has an austerity crisis.” In 1996, Puerto Rico entered a ten-year period of gradual elimination of tax exemptions, which hurt the development of private industry. In response, the government started to sell vulture funds, selling sectors of the Puerto Rican economy to industries and individuals with private interests. This practice led to the implosion of the fiscal crisis, but because Puerto Rico is considered a “non-incorporated territory” by the United States’ government, it cannot declare itself in bankruptcy and it is obliged to pay the debt as its utmost priority. Negrón-Muntaner identifies this method as the American model of “new extraction of colonial capital: debt.” Among the most worrisome, “this new modality of capital does not need Puerto Ricans,” leading to the concept of “Empty Island,” meaning, both the Puerto Rican economy and government work solely to pay the debt and not for its inhabitants.

Part of what inspired the project was the lack of trust that Negrón-Muntaner noticed in Puerto Rican society towards media and government platforms, and between the people. The project was reformulated after Hurricane Maria due to the lack of governmental support during the disaster. The Puerto Rican people developed a solidary economy in their communities and people survived “practicing an economy of exchange.” Puerto Ricans are capable of subsisting economically independent from the colonial capitalist economy that led to the crisis. Negrón-Muntaner asked herself “How does money acquire value? Can it be destructive?” and concluded that money, in essence, serves to “facilitate relations between people.”

While recruiting businesses to participate in the project, Negrón-Muntaner noticed that no one had heard of the concept “social currency” before but that they all understood it immediately. In the midst of the economic crisis and in spite of being informed that they could lose money and time for eight days, most businesses agreed to participate. The selection of the people that would go on the bills was based on four values: equity, solidarity, justice, and creativity. They also made an ATM machine called VYC (“Valor y Cambio,” or Value and Change) for it to be a physical experience.

In order to get the bills from the ATM, the participants had to answer the question: what do you value? The project was a success and people waited for hours to get the bills, being moved by answering the question, at times to the point of tears. From this surged what Frances Negrón-Muntaner recognized as “decolonial joy” defined as, “the possibility of a different future, one in which neither colony nor colonialism can define happiness.” Negrón-Muntaner witnessed this joy in “the exact moment when the participant received the bill, particularly the one they had waited for.” One of the participants, Eduardo Paz, Afro-Puerto Rican teacher, waited for the bill of the Cordero siblings and said: “This represents who I am,” expressing a dual valuation, “the world valued what he valued, therefore, the world valued him,” explained Negrón-Muntaner.

The people thanked her, not for her effort but for her joy. Negrón-Muntaner awards this to a triple plain of the Puerto Rican society caused by the austerity, Hurricane María, and the mass emigration. It has become important “to share not suffering, but joy.” More than a thousand participants did not use their bills, and they said it was because the bills were beautiful, they saw them as something that upholds “the identity and cultural pride” and it freed them from colonial capital, since “the dollar is seen as colonizing,” explained Negrón-Muntaner. She noticed that both hope, which is future oriented, and joy, which is present oriented, surged simultaneously. This feeling persisted in some of the participants, with the Puerto Rican community Caño Martín Peña launching their own community currency (the first one in Puerto Rico) only months after this project.

Negrón-Muntaner did not create this project with the intention of creating a sustentative economic alternative to the US dollar in Puerto Rico, but as “a way of starting a conversation”. She considers that the substitution of one currency by another does not solve the problems of necessity and inequality in society, but by valuing the experience instead of the money this liberation she calls decolonial joy took place. There will soon be a movie about the project.

Abundance in the Hudson Valley

There is a social currency in our own Hudson Valley focused on strengthening the connections in the community and providing both businesses and individuals the freedom of get on economically in a local way and giving Hudson Valley the opportunity of generating earnings that remain in the valley and benefit our communities directly. The money exchanged from “Hudson Valley Current” remains circulating in the local economy and results in the development of the local economy.

Differently from “Valor y Cambio”, Hudson Valley Currents has an economic focus instead of an artistic-cultural one. While interviewing Chris Hewitt, the Co-founder and Executive Director of the currency, I discovered the magnitude of this currency’s impact and how it works inside our communities. Hewitt got inspired to start the currency to “Help people be more successful, reveal abundance, and inspire them to share and care for the community.”

With the goal of achieving local economic resilience, Hewitt recounts how he created this currency. “Working with a group of founders, we began to join our first members with our existing social media. Some of the first members were sponsors, since it is important to have something to purchase. Members bring people with them. Today we have around 400 members and almost 1 million currents have been exchanged in the past seven years,” narrates Hewitt.

For future participants, Hewitt talks of the importance of joining as a community, of his hyper-local focus, for the money to remain within the community for the most time possible and “this currency guarantees this.” It is the perpetual multiplier effect, says Hewitt and explains that six months ago he hired an Economics professor from Bard College, Leanne J. Ussher, to do a web analysis of Hudson Valley Current. She analyzed the information compiled in seven years and her analysis illustrated this perpetual multiplier effect. There are five affinity groups that support themselves mutually.

This currency is no longer solely virtual, since last October you can obtain bills at the Kingston Hudson Valley Current office. Among his aspirations, Hewitt wants to expand the current to more counties in the Hudson Valley. Right now, they are in Ulster and Dutchess, they have just expanded to Columbia, and have five members between Sullivan and Orange. “We want that wherever you go you see a Hudson Valley Current sign on the window,” dreams Hewitt.

According to Hewitt, Hudson Valley Current is the local currency with the most accelerated growth globally. Hudson Valley Current also has the Livelihood Magazine, a guide through the local economy, and the campaign “Satisfy Hunger”, a local initiative for food security. As federal law states, one current equates to one dollar and it pays taxes. 10% of Hewitt’s salary is payed in currents (his goal is to be payed 90% of his salary in currents) and for at least ten people to receive part of their salaries in currents too. Members use currents to pay rent, buy groceries, and in their daily lives.

You can live your own decolonial joy through the currents and in the meanwhile support the local economy. For more information about Hudson Valley Current and how to participate visit hudsonvalleycurrent.org.

Translated from Spanish by Nohan Meza COPYRIGHT 2020

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

Comments | |

| Sorry, there are no comments at this time. |